|

The Michigan Risk Score project in Brazil continues to collect data to externally validate the score in Brazilian patients. After collecting data on 3,067 PICCs in 6 months, Prof. Eneida Rejane Rabelo da Silva has more updates below… March 2019:

March/April 2019:

April 2019:

Finally, a message from the mentors! Being able to predict which patient may have a complication is the future of medicine. In this way, harm to patients can be prevented – even before a device or procedure is performed. Your work on the Michigan Risk Score Brazil project will help in ensuring that the MRS performs to protect patients. Thank you for all your hard work to help improve PICC care all over the world.

Our latest paper out new and available free at BMJ Quality Safety here explores use and outcomes of midline catheters in 12 Michigan hospitals. This study is quite possibly the largest prospective cohort study of patients that received midlines as part of clinical care. We followed 1161 devices for 30-days (with phone calls to patients at the end of this time) to understand experiences with these devices.

Our findings are interesting in that they show midlines are very different from PICCs in several ways: 1\ Dwell times are shorter: Almost 50% of devices came out within 5-days of going in 2\ The most common indication for use is Difficult Venous Access (which, incidentally) was among the top indications for PICC use when we began our work with MAGIC 5 years ago! 3\ Major complications including DVT and bloodstream infection are low. 4\ The most common complications were dislodgment, leaking and infiltration. 5\ Midline use varied widely across hospitals. How sick your patients are or how big or complex your hospital is didn't seem to predict your use of this devices. It seems that there are early adopters of midlines that use them a lot vs. others that are still hesitant. In almost all cases though, they were placed by vascular access teams. For me, the big takeaway from this work are that its a mistake to think of midlines as a homogenous group of devices. Unlike PICCs that all behave very similarly, how you insert a midline, the materials its made of, what you infuse through it and whether you care and maintain it in specific ways have a lot to do with how the devices last. They're certainly not as forgiving as their longer counterparts! Case in point: at one of our hospitals, midlines stay in place without problems (they are literally drawing blood from the catheters) at 30-days without issues. At another, they are lucky if they get five days of use. Understanding what drives these differences is going to be important work that needs to be done. But judging from the outcomes, they clearly have a role in our patients. How to use them safely and ensure that benefit >> risk is going to be key! Look for more work on midlines coming soon from our HMS collaborative! It's the beginning of a New Year and this means it's the beginning of new and great things. I am delighted to tell you that the MAGIC app has been downloaded over 8,000 times since it was first released two years ago. That may not be much by the standards of the latest game on the iTunes store (!) but its not too shabby for a medical app that aims to improve vascular access decisions!

Personally, it's great to hear that the App has been a key way to interface with the evidence and see physicians use it to make decisions. I have even heard that some health systems have moved to make the App mandatory before ordering a central venous catheter! In my wildest dreams I would never have thought this would happen! Thank you for the success of MAGIC! So, how do we make a good thing better? Simple - by asking all of you! We have received great feedback from many of you - the users of the App - about what we could improve on! So we've started to put together an update and refresh of the application. Some things to look for: - A new user interface with cleaner graphics and smoother feel - Updated workflow around patients with chronic kidney disease - A specific section of the App dedicated to TPN - Improved access to the original MAGIC Guidelines with more details and images from the full paper - And many more tweaks and fixes! When will the MAGIC happen? Well, we are doing this all internally so it will take us a bit to get the updated App (for both iOS and Android) out there. As soon as it is ready - we will let you know! Make sure you bookmark this page and watch this space! I look forward to hearing what you think of the update in the weeks ahead! And if you haven't downloaded the original MAGIC app yet, it is still available here. In November of 2018, I was interviewed by Drs. Ludovico Furlan, Giorgio Costantino, and Nicola Montano from the University of Milan. They contacted me because the Italian Society of Internal Medicine Choosing Wisely Campaign has incorporated the Society of General Internal Medicines Choosing Wisely recommendations related to PICCs. The team at the University of Milan is seeking to develop an educational program to improve central venous access and decision-making related to intravenous devices centered on MAGIC. Their vision is to educate residents and trainees on this recommendation through an online training course which would include decision-making related to vascular devices. I was delighted to share as much as I could with them. They asked some difficult questions! The interview and their questions (posed to me in English but translated here in Italian) is here! Enjoy (Godere!) The Michigan Risk Score validation project in Brazil is heating up! Since the last time we spoke with Prof. Eneida Rejane Rabelo da Silva, the PICC-Brazil Research Group has been hard at work. Here is what has happened since our last update.

Dr. Naomi O'Grady is a Senior Staff Physician at NIH and first author of the CDC Guidelines. She recently wrote a thought piece for Annals of Internal Medicine. We sat down with her to have a discussion about her article, central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) and measurement of this infection. Here are some of our excerpts:

VC: CLABSI has become such a volatile HAI. Given all the penalties and public reporting, no wants to have one. And hospitals that do have one now have to report these data publicly - leading to all kinds of problems. What are your views on the policy for CLABSI reporting in the US? What impact has this had? NG: The precise impact of public policy on CLABSI is unclear. In 2008, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) instituted financial penalties for hospitals with higher-than-expected CLABSI rates. At least two studies have reviewed the effects of such penalties on CLABSI rates: one suggested no effect, while the other reported a decline in infection. Whats important is to understand whether financial penalties have actually changed practice at the bedside. One fear is that such policies may dissuade clinicians from ordering blood cultures in patients with central venous catheters (CVCs). Less testing for CLABSI, in turn, could result in lower detection of CLABSI—improving hospital performance without changing patient outcomes. In addition to the non-reimbursement policies instituted in 2008, several states instituted public reporting of hospital-acquired infection rates for hospitals. In 2004, only 4 states had such a requirement, but in 2016, 38 states and the District of Columbia required public reporting. Again, it is difficult to ascertain how these policies impact care at the bedside. But, by design, they pressure hospitals to reduce CLABSI to zero. It is well known that economic incentives to influence practice can lead to unintended consequences. In the case of CLABSI , financial pressure could lead to changes in the way that CLABSI is defined or detected. VC: Lets talk a bit about measurement - there are challenges there, right? NG: Well, determination of CLABSI rates is inherently dependent on the definition of CLABSI and methods used for case-finding. Changes in either of these influence the interpretation of CLABSI data over time. The National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) definition of CLABSI includes three components: 1) The presence of a laboratory confirmed bloodstream infection; 2) in a patient with a CVC; 3) with no alternative source of bacteremia identified. The last of these components is especially subjective. Policies tying public reporting to non-payment could influence hospitals to adopt an intense explanation for “alternate sources” of bacteremia. Of note, such relentless searches did not occur when financial consequences were not present. Thus, while CLABSI rates over the past 2 decades may have been over-estimates of the actual rates, it is plausible that current accounting strategies may be underestimating CLABSI, especially if some are attributed to other sources of bacteremia. Even with rigorous application of the NHSN definition, inter-rater reliability can be less than optimal. VC: What about the new mucosal barrier injury (MBI) addition? Has that helped in getting closer to truth? NG: The new mucosal barrier injury (MBI) category is intended to improve comparability of CLABSI rates by specifically classifying infections caused by certain pathogens as non-CLABSIs. The addition of MBI to CLABSI was a welcome change, especially for institutions caring for large numbers of cancer patients. But, as expected, retrospective studies showed an overall decrease in CLABSI rates when MBI cases were considered separately. Thus, whether lower CLABSI rates after 2013 reflect actual improvement in patient safety or artifact related to changes in classification remains unclear. VC: CLABSI rates have gone down over the past few years. Your comments make me wonder: is the decline real, or "fake news?" NG: Many factors have contributed to changes in CLABSI rates over time. Some changes have made a real impact on patient care. Conversely, others may have altered the numbers without improving patient outcomes. VC: So what should clinicians and hospitals do? NG: Facing this uncertainty, I think our focus should continue to remain on ensuring CVCs are used for appropriate indications, removed when no longer necessary and bundled strategies for CLABSI prevention are rigorously implemented. In addition, hospitals should internally monitor CLABSI rates over time. In this way, internally consistent data rather than comparisons with other institutions employing alternative definitions or measurement strategies may be used to assess progress. VC: Any closing thoughts? NG: Perhaps we will never know how much of the recent improvement in CLABSI rates is real versus how much is “fake news.” Regardless, we must continue to refine our definitions and data. After all, we should be zeroing in on zero when it comes to CLABSI. Our patients count on it.

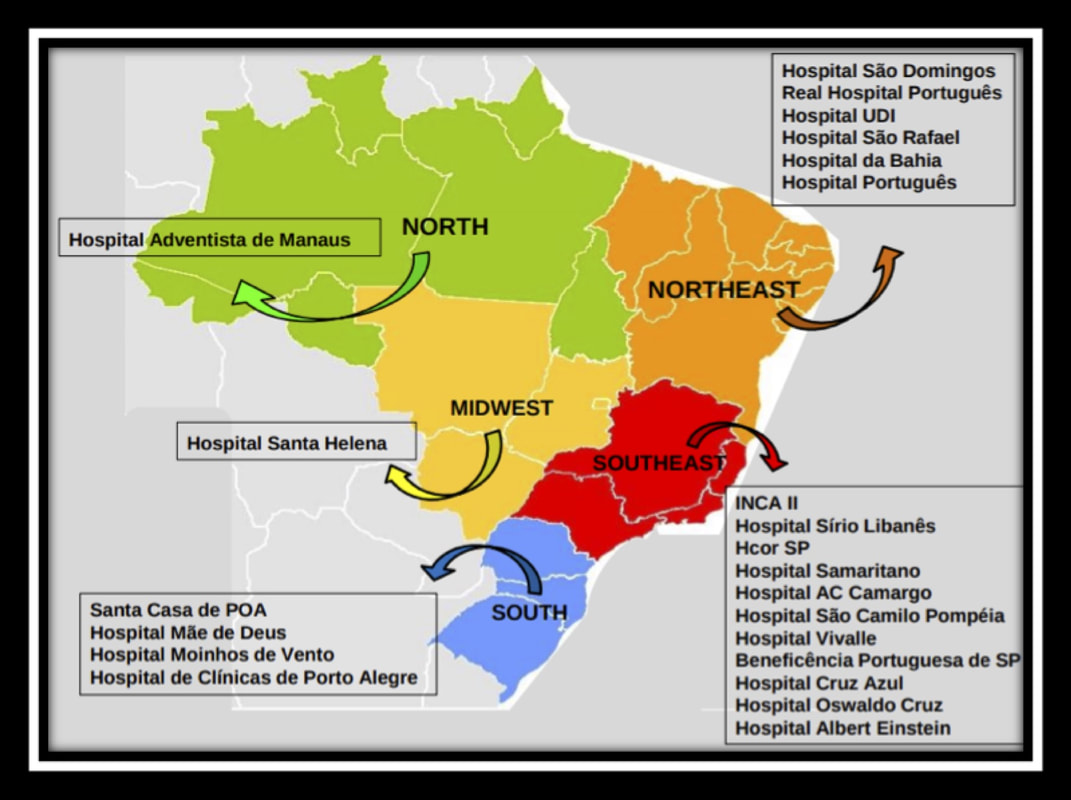

Validation of the Michigan Risk Score for use in Brazil - A Multicenter StudyWe are delighted to conduct this multi-center study in Brazil with the partnership of Prof. Dr. Vineet Chopra, from the University of Michigan, who was responsible for the development of the Michigan Risk Score (MRS). The MRS aims to estimate and predict risk of Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC)-related thrombosis. Although the score was developed and internally validated, it has not yet been externally validated. In fact, in Brazil, no tool to estimate the risk of PICC thrombosis currently exists. Therefore, in this study, we propose to externally validate the MRS and evaluate its applicability to the population in Brazil.

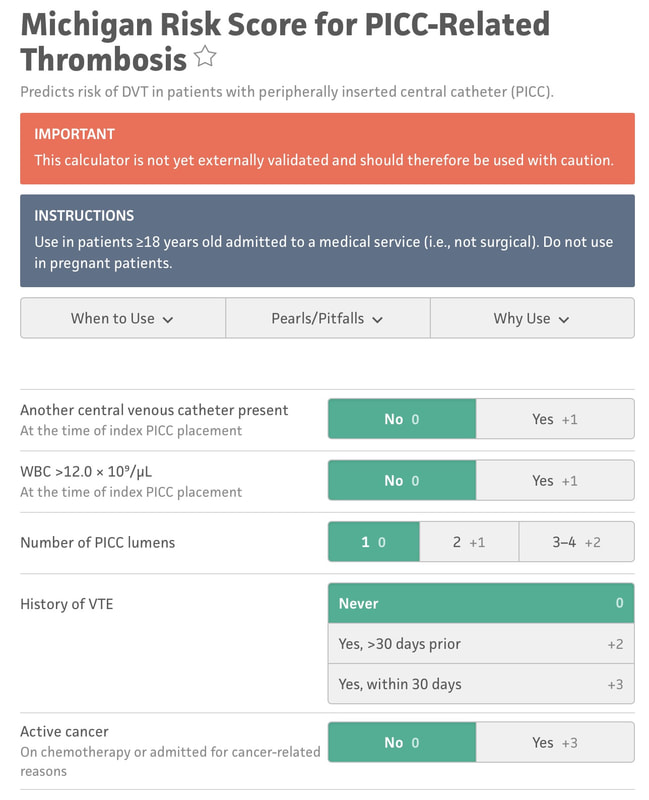

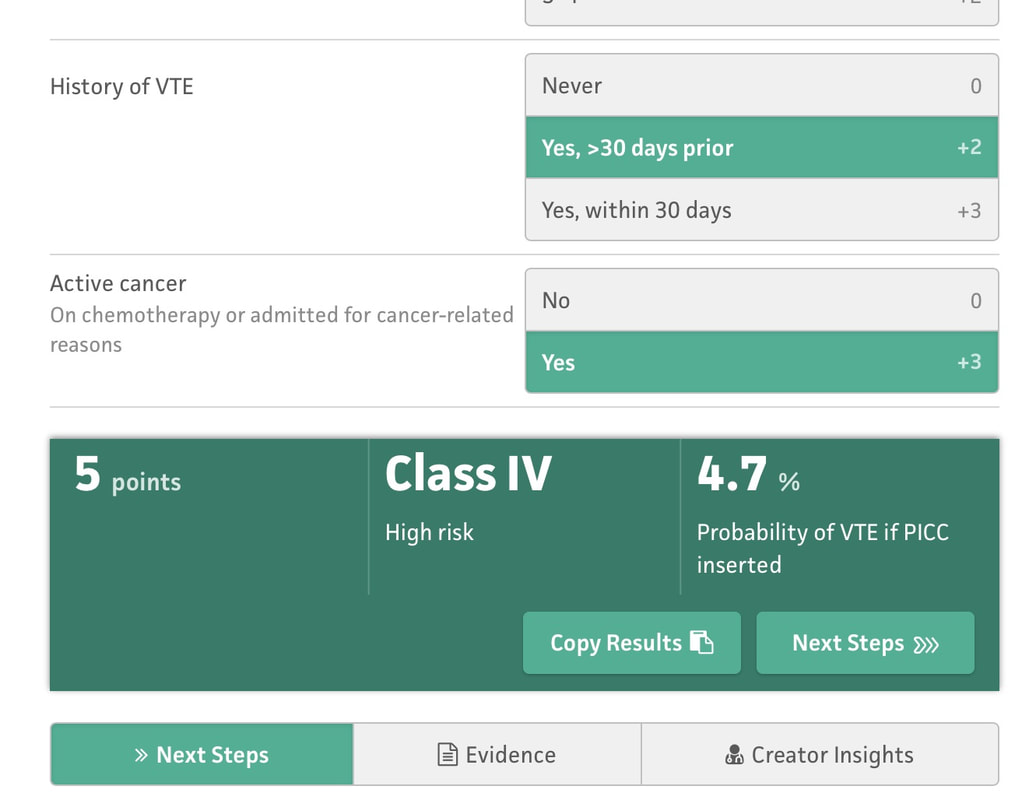

We will conduct this study in 23 institutions in Brazil, with representation from all of the 5 major regions of the country (Figure). All participating center have agreed to developing a dedicated team to this project, members of whom will be responsible for data collection. All researchers will use a standard protocol for data collection and will be trained by the coordinating center prior to starting the study. In order to ensure ongoing collaboration of this group to continue to study more vascular access questions. All of the principal investigators (PI) are registered in a PICC-BRAZILIAN RESEARCH GROUP (http://dgp.cnpq.br/dgp/espelhogrupo/2184405437599410). This group will not only collaborate for this project, but can now engage in other projects moving forward. The researcher responsible for this project in Brazil is Prof. Eneida Rejane Rabelo da Silva, RN, ScD (CV: http://buscatextual.cnpq.br/buscatextual/visualizacv.do?id=K4701295A6) with her research group from the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre and the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. We estimate that we will be able to accrue a sample size of 24,150 patients (including 5% of losses) in order to validate the MRS score. We propose to collect these data for analysis over an 18-month window. I hear it everywhere I go. "I wish I could have known that patient would have had a DVT..." "If only I could have done something different before ordering or placing the PICC..." "I had this feeling they were high risk, but I wasn't sure and it seemed like a reasonable choice..." All of these are aphorisms of the sinking feeling when you get the call: the ultrasound is positive, and the patient has a PICC-DVT. We know there are evidence-based ways to prevent this:

But even if you follow all of the above recommendations - some patients will still have a PICC-related DVT. Is there a way to know? I'm referring specifically to a crystal ball here - a way to be able to predict who will have a DVT and who won't, if you follow best practice. That is what the Michigan Risk Score (MRS) does.... We looked at over 20,000 patients and separated those that had a PICC DVT from those that did not. Then - we went back in time to before the PICC was placed. What was it about those that had a DVT that different substantially enough from those that did not? Was there a signal? We certainly found one - and published this for others to see/use. Here are the risk factors: 1. Presence of another CVC when the PICC was placed. 2. WBC count > 12, 000 at the time of PICC insertion 3. Number of PICC lumens 4. History of Venous Thromboembolism 5. Active cancer Selecting each of these displays a final score and risk class (I-IV, IV being highest) that can then be used to determine whether the PICC is the best choice for the patient. This is particularly true for those with cancer or patients who have had prior VTE - since avoidance can be the best treatment in this subset as shown in the picture below. There are a number of resources that can make this easier for you to apply on a day-to-day basis - before the PICC is ordered or placed (see below for links). The MRS is now being validated through the leadership of a number of brilliant investigators and committed hospitals in Brazil. The project will likely take 18-24 months but will provide invaluable information about how the MRS performs and whether it can be improved. It's through tools like this - the proverbial crystal ball - that our patients will be best served. See more information about the MRS and find a handy calculator here. The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC) is an evidence-based series of recommendations that provide guidance on how best to use, manage and care for vascular access devices. MAGIC is now being used in hundreds of hospitals across the nation, and many hospitals overseas. But the question remains: does MAGIC work to improve patient safety? Until recently, we all wanted to believe that it did. And belief was all we had... But thanks to work by an inspirational physician and her team in a Michigan Hospital - now we know. Dr. Lakshmi Swaminathan and her Vascular Access team led a real world "validation" study of MAGIC. Validation is a scientific process where a method or idea is removed from it's origin (or derivation) and makers and placed into a brand new environment to see if it "works" as designed. Often used for statistical models for prediction, validation serves to affirm that the method or research described does what is intended - while providing valuable insights about what worked and what didn't and why. In an article published in this months British Medical Journal - Quality and Safety (BMJQS), Dr. Swaminathan and her team report findings following an interrupted time series implementation of MAGIC in their hospital. To ensure findings were rigorous, they compared their results to ten other hospitals involved in the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety collaborative - members of which are all focused on PICC use and outcomes. Thus, this study answers a specific and important question: among hospitals all working to improve safety and use of PICCs, does adding MAGIC make a difference compared to baseline? The results: absolute rates of inappropriate PICC use dropped 26% more than other sites. Even after adjusting (or taking into account) patient complexity, hospital characteristics and other improvements - MAGIC improved PICC appropriateness by 13.8%. Importantly, PICC complications also decreased at a substantial rate (34%) compared to other hospitals (26%). In short - MAGIC worked to improve PICC use and patient safety, and does so in ways more than other quality improvement work might suggest. But (as with all real world research) there are some important caveats. First, although the authors used a robust study method, this was not a randomized trial. Thus, unmeasured factors might explain the difference across the study hospital vs. other control sites. Second, multiple components of MAGIC (an electronic tool, algorithm, educational roll out and nurse-based checklist, etc.) were used; which component was the most critical (or was the "active ingredient") is not known. And finally, although the reduction in complications was great and outpaced that of other hospitals - it wasn't good enough to achieve statistical significance for CLABSI and DVT. A larger study with more patients is needed to better understand this aspect. So what does this study add? A few key things: first, we know from this work that implementation of MAGIC leads to improved PICC appropriateness and outcomes at a hospital other than where it was created. This is good news, as other hospitals (particularly community hospitals where this work was performed) that use MAGIC are likely to see similar benefits. Second, we know that MAGIC reduces complications from PICCs more than hospitals using other QI approaches: thus, hospitals struggling with occlusion, CLABSI and DVT might particularly benefit from using MAGIC. And finally - this study tells us that a vascular access team driven initiative can have huge payoffs to a hospitals bottom line. The implementation study in this facility was driven largely by the vascular access team - and saved hundreds of thousands of dollars for this facility in terms of reduced complications and device appropriateness. That's the bottom line for many C-suite level leaders - and that helps answer why we need more vascular access teams in the country! If you're interested in learning more, check out our CLABSI and DVT Cost Calculator for a savings estimate! But perhaps the best part of this work is that it lives beyond a paper in a journal. The team at this hospital continues to experience great reductions in inappropriate PICC use (including in ICU patients) and outcomes (all VTE in the hospital) as shown in the slideshow below! And the patients are simply better for it! That, perhaps, is the greatest reward of them all! You'll find some key components of the MAGIC study in the links below, and you'll find a copy of the published article there as well. Please do share widely and post your comments and feedback. And remember - the easiest way to use MAGIC is through the app - which is available for free here! Get your MAGIC On!

We all know that central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) are common, costly, morbid and lethal. While many interventions such as the checklist, bundle, and chlorhexidine-based products have been introduced to prevent CLABSI, the struggle continues for hospitals across the country. And for many – the battle is not being won. One reason why CLABSIs are so hard to tackle is because the root causes of these infections are multifactorial. For example, not having the right team members or expertise to examine CLABSI cases represents a key gap in preventing future infections. Similarly, lack of support from leadership to implement change or trial new products can also be a barrier to infection prevention. In short – hospitals need a tool to diagnose their approach to CLABSI to understand what they can do better and where limited precious resources might be best directed. Until recently, such a tool did not exist. However, we at the Patient Safety Enhancement Program at Michigan Medicine have developed a first-of-a-kind tool to help hospitals “diagnose” their CLABSI prevention efforts. Called the CLABSI Guide to Patient Safety (or, CLABSI GPS) this tool allows hospitals to understand what they are doing well – and what they are not. Developing following years of research, site visits and data analyses, we hope many members of the patient safety team – vascular access teams, infection preventionists, hospitalists, infectious disease physicians and various subspecialists – will use the team to help inform their CLABSI prevention efforts. Tell us what you think about the CLABSI GPS by dropping us an email here. And thank you for working hard to keep your patients safe!

|

AuthorsBlogs written and edited by Vineet Chopra unless otherwise stated in the header. Guest blogs are identified accordingly. Archives

May 2019

Categories |

||||||||||||||||||||